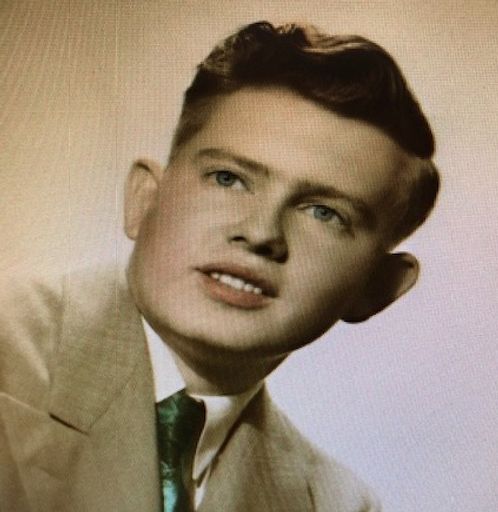

J N Ball

August 4, 1932 — May 23, 2020

J N Ball

J.N. Ball, 87, of Mountain Home, Arkansas died May 23, 2020 of multiple myeloma.

He was born August 4, 1932, to Michael and Sally May (Battle) Ball in Byron, a tiny Arkansas town 13 miles outside of Salem. He spent his long life being asked what name lay behind his initials, but the letters were the whole name. According to family lore, he had grandfathers on both sides with those initials, so he was named "J.N." to honor them both. His friends called him "Jay."

There was nothing great about the Depression in the Arkansas hill country. Jay had vivid memories of brutal poverty. His family survived on turnips when other crops failed one year; even the milk tasted of turnips because there was no other fodder for the cows. They lived in fear that his late older sister, Maxine, would starve. During World War II, he could scrape up enough money from chores or picking cotton to walk the long road to town for an evening of roller skating or movies. He could recount strange and colorful tales of Arkansas: an uncle who shot off his leg while hunting water moccasins; the blind uncle who played virtuoso fiddle; the time he cowered as a boy behind a mulberry bush as a tent revival preacher baptized his mother in the river.

Jay dreamed of escaping Arkansas with his best friend and cousin, Whorton Cochran, to pick apples in far-off Washington state. Whorton's death in a freak accident, not long before the teenagers could hit the road, was a loss that Jay never got over. They will rest forever, not far apart, in the Byron cemetery.

Instead of apples, Jay picked the Navy after high school, and served as a radar operator aboard the USS Bayfield, an attack-transport that saw action in three wars. Jay served in two of them, Korea and Vietnam. He was part of the 1954 mission to rescue refugees during the partition of Vietnam. Along with his foreign service, Jay was proud of his role in the dramatic rescue mission after a Pan Am passenger plane crashed off the coast of Oregon. His work in the radar room helped the Bayfield find life rafts bobbing in the open ocean. Nineteen of the 23 people on the aircraft survived.

Jay's service was a lifeline to his parents. Most of his monthly paychecks went directly back home--and most of his card winnings, too. And his service was a source of pride forever. No matter how many children he eventually crowded into his car, Jay never passed a hitchhiker in uniform: Make room, kids.

With a single suitcase and one change of clothes, Jay arrived in Kansas City to find a job. He walked until he found a house advertising rooms to let. He told the woman who answered the door he had no money and no job, but he would find one and pay her back. "You look like you have an honest face," she said. "Come on in.” Jay found work at Katz Drug Store and made good on his promise. Later, he worked as the weekend handyman at apartment buildings on Kansas City's famed Country Club Plaza in exchange for a place to live. Important themes of his life--honesty, hard work, self-reliance, a nose for a nickel or a dime--were rooted in these years.

In Kansas City, he met Marilyn Sue Mohler, a brainy farm girl from Northwestern Missouri who had recently graduated from college. On a sunny day in May, they held their wedding reception on her family farm. They had five kids — four within four years. He had a career as an electrician with the telephone company. It was a testament to Jay’s dedication as a father and husband that the stoic farmers in Marilyn’s family came to view him as a son, brother or nephew.

They were still in love when she died in 2005. He never stopped loving her. Marilyn’s ashes rest on Long’s Peak, a grand site above the YMCA of the Rockies where she and Jay worked for 15 summers as friendly faces at the front desk and gift shop.

Jay was an unusually hands-on father for his time. On a road trip with his family in a pop-up camper behind a blue Dodge station wagon, a man at a campsite in South Dakota remarked on how much time Jay spent playing with his kids. "It's the only way I can keep them from fighting," Jay answered, with his sly humor. But it went much deeper than that. Jay coached baseball, led Scout troops, organized candy sales, worked at school carnivals, led scrap newspaper drives--not just for his own children, but for much of Kansas City's old East Side. Late in life, Jay dreamed of little boys yelling for his attention: "Mr. Ball! Mr. Ball! Mr. Ball!" It was so appropriate, because he made room for fatherless and under-parented kids who wanted to go on a camp trip, or learn to swing a bat, or see a big-league ballgame. Once, Jay started to build a boat for himself. He learned of boys who had no footlockers for camp. He tore up the boat and made boxes from the pieces.

His own children received less sympathy. Jay could be stern as he taught them to work hard and spend frugally. He brooked no slacking over swim lessons, multiplication tables, or weeding in the garden. He loved books, and passed that along through frequent visits to the neighborhood library. He loved God, and passed that along by example.

Jay could feel like a hero to his children. "I remember how our Cub Scout team played a pickup game against the boys from Lister," his son Joel recalls. Jay stepped up to the plate, and on the third pitch hit it over the fence for a game-ending grand slam home run. Like all fathers, perhaps, he could also be a puzzle.

He loved sports, splurging on a pair of season tickets to the Kansas City Chiefs. He was present at Municipal Stadium on Christmas Day, 1971, for the longest game in NFL history. He had been feeling lousy and coughing a lot in January of this year as the NFL playoffs got underway, He perked up one day on the phone with one of his daughters: “Maybe I will live long enough to see the Chiefs win another Super Bowl.” Jay’s children are thankful he did. Nothing could match the St. Louis Cardinals baseball team in his heart, however. Back in the days before television, when Jay formed his loyalties, the powerful signal of St. Louis radio made Cardinals fans in every Ozarks family.

J.N. Ball was preceded in death by his parents and by two sisters, Joyce Maxine Williams and Nina Rodgers. Other siblings died in infancy in the 1920s. He leaves his five children: Tammy Ball (Rusby Adams), Joel Ball (Joy Dabby), Jeana Ball (Abel Lopez), Karen Ball (David Von Drehle) and Melanie Ball. His 12 grandchildren span the continent: Katie and Zachary Brewer-Ball; Zane and Madeline Adams; Andrew Ball and Christopher Pine; Henry, Ella, Addie and Clara Von Drehle; Skylar and James Ball.

His grandchildren are thankful for the (very few) times they ever beat him at cribbage.

He also leaves three great-grandchildren, and a dear friend in his later years, Fannie Caldwell.

Jay would cringe if anyone sent flowers. You can take the boy out of the Depression, but you can't take the Depression out of the boy. Instead, he would urge people to save a dollar in his memory. And then go do a good deed.

Guestbook

Visits: 60

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the

Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Service map data © OpenStreetMap contributors